Deviation Actions

I’m thinking about The Renaissance Express. Like, a lot a lot. And one of the things that bears some thought it the future of the English language.

What will English look like five hundred years hence?

If we compare the future evolution of English to the past, people in the 26th century will speak something about as different from people in the 21st as Early Modern English is to us. That is, a time-traveler from five centuries in the future would be more or less understandable, but would speak with a very strange accent. But strange in what way, exactly?

A lot depends on the history of the future. What countries are most influential and powerful? What populations add themselves into the Anglophone community? How does technology change the way we use our language? The following are several possibilities:

(0) Nobody will speak English

What if the Chinese invade? Or the Arabs? Nahuatl in the 15th century was a great language of trade and culture, after all, and how many people speak it now? Maybe in 500 years we’ll all be speaking some other language, and English will either be the language of a few local underclasses or entirely extinct.

I guess it’s possible, but I doubt it. In the absences of an apocalyptic event that blasts us all back to the stone-age, the winners of the next five hundred years of history will be the people who make the most inventions. The people who make the most inventions will be the people who have the most educated people trying to solve problems. English is the global language of education and invention, and its hard to imagine what other language might replace it. Yes, China and India are very populous, and might well deliver enormous waves of educated inventors, but Chinese and Indian inventors speak English to each other. Of course, they might not speak English in any way familiar to a 21st-century American…

(1) Universal Globish

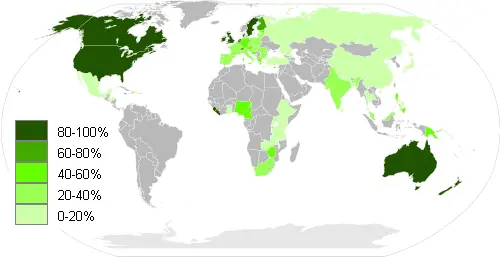

As many as 100 million people speak English as a foreign language, compared to about 300 million native speakers. It’s easy to imagine that the number of non-native speakers continues to grow until, while most people in the world speak English, few of them speak it as a mother tongue. The language they speak is simpler, more universal, stripped of regional differences, a somewhat artificial language intended only to conduct business and education. English-speakers must learn this new “Globish” in order to communicate with colleagues abroad, but it isn’t that hard.

The problem I have with this scenario is that while there certainly can be (and in fact there is) a pidgin trade-language based on English, it isn’t really universal (speakers of European pidgin English have a hard time understanding speakers of Indian or Chinese pidgins). People could make an effort to create an international standard pidgin, but that language wouldn’t be comprehensible to English speakers. Languages don’t usually form unless the people who speak them have some sense of common identity. People who learn English as a foreign language have no such emotional attachment to the language, and are happy to accept corrections from native English speakers.

So I don’t think the non-native speakers will go off and create a new language. They will probably all converge on a standard dialect. But what will that dialect be?

(2) “The internet will still be dominated by English speakers, but they’ll have an Indian accent.” Charles Stross said that, and it’s hard to disagree. Once India’s huge population achieves educated middle-class status, their way of speaking English with dominate the global Anglosphere. People in the US or UK might speak local dialects to each other, but the standard dialects of education, wealth, and influence will sound Indian.

(2) “The internet will still be dominated by English speakers, but they’ll have an Indian accent.” Charles Stross said that, and it’s hard to disagree. Once India’s huge population achieves educated middle-class status, their way of speaking English with dominate the global Anglosphere. People in the US or UK might speak local dialects to each other, but the standard dialects of education, wealth, and influence will sound Indian.

My problem with this scenario is that although many people in India speak English, very very few (0.022%) speak it as a mother tongue. When India becomes a world power (and I don’t doubt that it will), we might very well see an international rise in the popularity of Hindi, but Indian English might not have any more influence than other English dialects than Anglo-Norman had on other dialects of French.

(3) English in the 26th century might look like like Latin in the 10th century and likeArabic in the 21st. There is an international standard English based on some classic works (like the Kage Baker’s “Cinema Standard“), but different groups of people will be speaking increasingly incomprehensible dialects in local and informal situations.

The problem with this prediction is it actually bucks a trend we’ve been seeing since the invention of the radio, which is a decline in differences between regional dialects. There are some exceptions, but generally people are now in better communication than ever before, and their dialects are merging. This is true even for the two most influential English dialects (British Received Pronunciation and General American), which are actually growing together, not apart.

(4) Universal translators make everything irrelevant.

One interesting new wrinkle technology will introduce is machine translation. Even if we never get any better at machine translation than we are now, people will easily be able to “re-tune” materials in a foreign dialect into their own. We already do something similar with British books published in the US (a simple word search that replaces “lift” with “elevator” and “dustbin” with “garbage can”).

If everyone uses technology to filter out foreign dialects, we could see a combination of all the scenarios above, where speakers of increasingly divergent “home languages” speak to each other in a simple, machine-assisted international standard based on the norms of Indian programmers.

Or something completely different. What do you think will happen to English in the next five hundred years?